Image via Wikipedia

Image via Wikipedia Jeter (Photo credit: danic)

Jeter (Photo credit: danic) Image via Wikipedia

Image via Wikipedia Derek Jeter (Photo credit: Keith Allison)

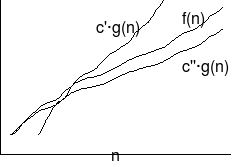

Derek Jeter (Photo credit: Keith Allison)It's essentially a debate over the merits of quantifying everything and using projections to run your team as opposed to taking a more subjective (though no less rigorous) approach and researching players without needing a precise projection for each one.Issue: INTUITION v. QUANTS

Intuition

“It's true I have a vague projection, but who cares if I have Jeter for 22 steals or 25? I know it's just a guess anyway. I put him at 22-ish steals if I bother to think about it which I don't when I'm drafting. The more important thing in many ways is my overall impression of Jeter compared to the shortstop pool, not just in numbers, but in reliability, durability, etc. I'll target him as a nice piece of my overall puzzle. I'll determine how important he is based on league depth, quality of shortstops, etc.”

versus

Quants

Sure, all projections are a guess, and we can only achieve a certain level of accuracy, but by watering our projections down further, all we’re doing is reducing that accuracy. Even if all you have is a rough idea about a player in your head without a precise projection, you implicitly do have some sort of projection for that player. And whether you have an explicit numerical projection for a player or not, you’re still obligated to pay for that player’s numbers. And at the end of the year, those numbers will have been worth X dollars (whether we know – or care to know – precisely what X is or not).For more details and analysis, then click here

Click here and go to 4th paragraph for links to threads of this discussion

- Does it confer an advantage to have a tighter model for converting stat lines into dollars?

This one seems self evident—of course it does.

- How much advantage does a better conversion/translation tool confer during the draft?

Well, this is the question of whether Phipps is a good card counter or not. Or, to add another analogy here, having the best feel of what raw materials should cost will not necessarily make you the most efficient builder.

So, in addition to the elastic supply and demand in a fantasy draft/auction setting, one must assemble value in the correct way. The efficiency of correct pricing can quickly evaporate if you make errors in estimating how much of each material you need to build your structure. In a fantasy league, margin of victory is meaningless, so the holy grail is to get maximum value distributed with maximum efficiency, which is to win every category by a single unit. However, more likely is that you wind up with surplus bricks but are woefully short in mortar; at that point is doesn’t matter if your whole lot of materials is appraised for more than anybody else’s lot, or if bricks are more valuable per unit than mortar. The surplus bricks are worthless to you and unless you can turn them into something else, you lose.

How do you beat an expert gamer in a math game?

Let’s start with one basic premise of game theory and one fact about computer programming, neither of which are fields in which I’d consider myself an expert. Game theory dictates that you never want to alter your play in a manner that will cause a poorly playing opponent to react in a way that will probabilistically improve his play. Computer programmers note that one of the most difficult things to program a computer to do is to generate random numbers; what often appears to be a random string is really just a very small string within a much longer string, for which a pattern exists.

And, while we’re at it, let’s throw in the good ole Voltaire quote: “The perfect is the enemy of the good.”

How do we judge who performs the best in a fantasy league, and what is the goal when developing your team?

Now, we get to my real question.

Two of the analogies mentioned throughout this debate were chess and stock market. These were chosen as examples to reflect subjects for which processing power was the linchpin in figuring things out and where the inputs were just so numerous and diverse that a model was nearly impossible to build at all. There’s one other difference between chess and the stock market, one which fantasy baseball actually marries though, resulting in a difficult to resolve question.

In chess, you are playing a one-on-one game, in which you must simply beat your single opponent; there’s one winner and one loser. To succeed in chess you must win way more often than you lose. In the stock market, you are really competing with the field to call yourself successful. You don’t ever need to have the biggest day, or week, or month of any other trader, you just need to win more than you lose and be consistently profitable over time. In fantasy baseball, you play against the field, but there is only one winner. This dynamic affects the appetite and rational tolerance for risk.

I don’t think a model-based approach will necessarily be risk-averse. In fact, I think a good model will aim to be risk appropriate. But, as long as a quant is competing against a field of “genius” sharps, it seems plausible that nearly every season several of the geniuses will take on what objectively derived and rational models will deem too much risk and one or more will hit on a bunch of those picks and win by outperforming the market. My biggest fear about the quant approach is that it’s a path to being a perennial runner-up.

I have no doubt that the quants will “get their money in good” with high frequency even right off the bat. They could do this just on the strength of math even if they didn’t know much about baseball. But that doesn’t mean they will win the league outright with any consistency. If you are playing against an opponent who sees a second-place finish and a last-place finish as the same exact thing, how do you consider that in a model?

I question whether the genius drafter and the quant are actually competing strategies, or discreet paradigms, one being a road to perennial contention but smaller margins for over or underperformance, and the other being more volatile in terms of range of outcome, but more anecdotally successful. And this is the question that begs the elephant-in-the-room meta-point; how do we judge success in the fantasy baseball arena?

No comments:

Post a Comment